The world’s oldest known mummies have been identified in Southeast Asia and southern China, where smoke-drying preserved the dead up to 12,000-14,000 years ago, far earlier than the famed traditions of Egypt or the Chinchorro of South America. This discovery reframes early human ritual life as inventive, resilient, and deeply bound to memory and place.

Discovery and technique

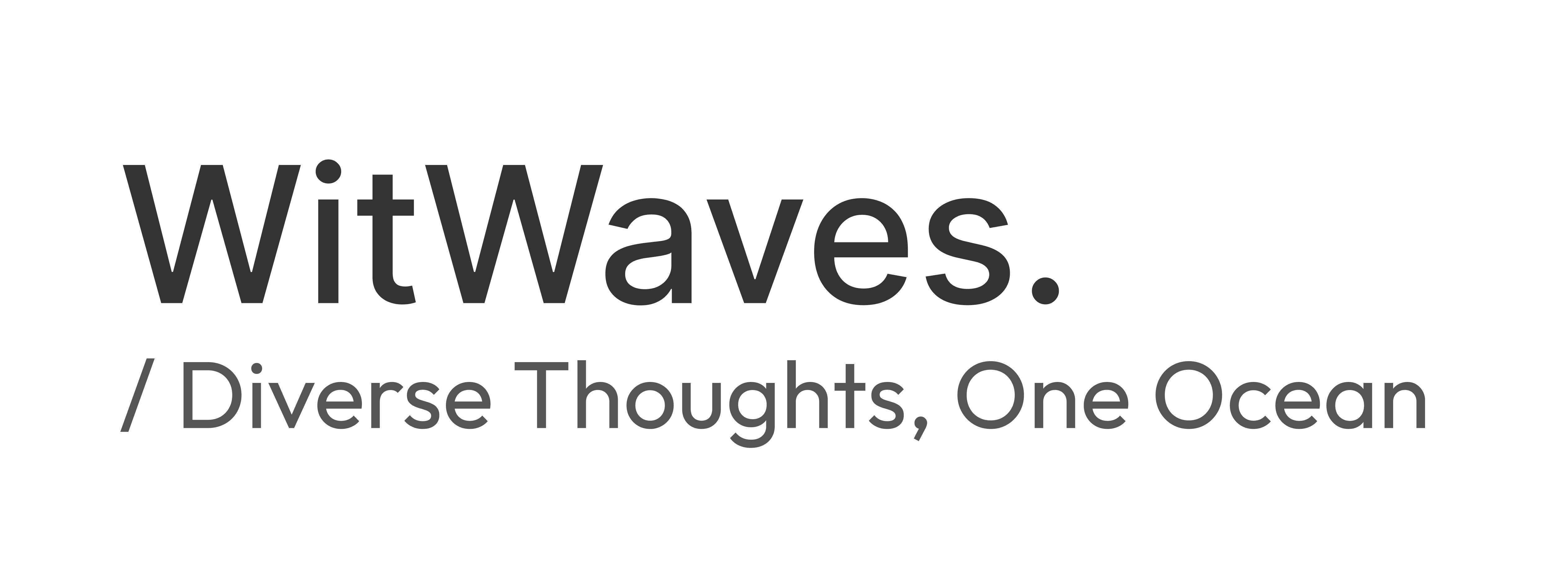

Archaeologists working across China, Vietnam, and other parts of Southeast Asia documented burials where bodies were deliberately smoke-dried before interment, an approach tailored to halt decay in hot, humid environments. Individuals were often bound in tight, crouched postures, sometimes knees to chest, then slowly dried for weeks or months over low, smoky fires to dehydrate tissues and suppress microbial activity.

The scientific evidence

Analyses of nearly fifty-plus skeletons revealed soot, superficial charring, and low-heat signatures incompatible with cremation, indicating careful, prolonged warming rather than burning. Techniques such as X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy helped confirm the distinctive heating profile, separating this method from the salt- and resin-based embalming known from later Egyptian contexts.

Cultural meaning and legacy

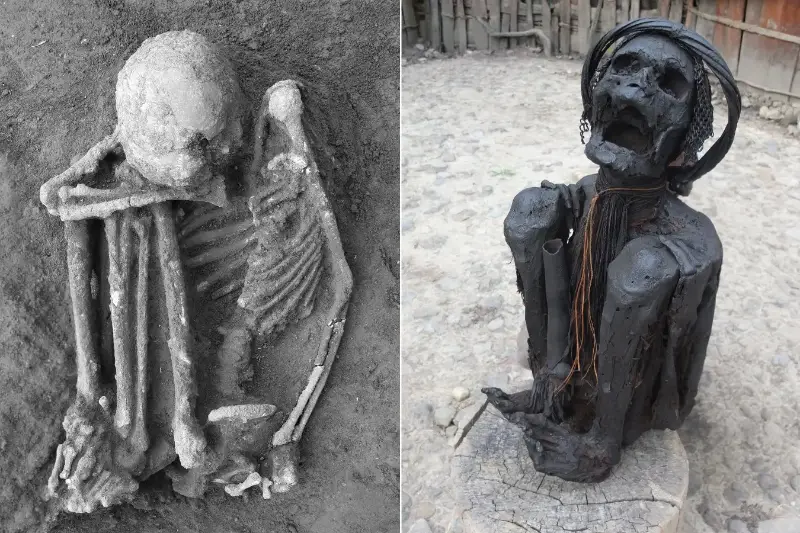

Smoke-drying was more than a technical fix, it expressed a powerful spiritual logic that kept ancestors close and identities cohesive across generations. Remarkably, echoes of this tradition persist today, as some Indigenous communities in Papua and New Guinea continue smoke-mummification for revered elders, maintaining them in homes for ceremony, remembrance, and teaching.

Timeline and global impact

- Southeast Asia: Up to 14,000 years ago; smoke-drying; hyper-flexed burials and rapid post-treatment interment.

- South America (Chinchorro): Around 7,000 years ago; complex embalming and reconstruction; long held as oldest.

- Egypt: Around 4,500 years ago, evisceration and natron desiccation, highly ritualized temple economy.

- The Asian finds predate Egypt by nearly seven millennia and the Chinchorro by at least five, extending the origins of intentional mummification far deeper in time and across a wider geography.

.jpg?alt=media&token=ceba94f4-320f-4593-af4c-0660da6070e0)

People, movement, and memory

Researchers link this practice to early waves of modern humans who settled Southeast Asia, populations ancestrally related to today’s Indigenous Australians and New Guineans. This supports a two-layer view of regional peopling, where older forager traditionsn and their mortuary innovations endured alongside later farming societies, revealing how belief, technology, and mobility intertwined.

Engaging facts

- Smoke-mummification is a creative solution to extreme preservation challenges in tropical climates, where heat and moisture accelerate decay.

- Scorch marks and hyper-flexed postures suggest bodies were bound for both practical handling and symbolic meaning during prolonged smoking.

- Modern parallels show living continuity: some communities still keep smoke-dried ancestors in domestic spaces for rituals, teaching, and communal identity.

- The discovery unites cutting-edge science with living cultural knowledge, illuminating an unbroken thread of remembrance stretching across millennia.

Why it matters now

These mummies tell a human story of ingenuity under environmental pressure and devotion to the dead as members of the living community. They show that the wish to remember, honor, and remain with ancestors is ancient, widespread, and adaptable, bridging early foragers and modern descendants through practices that make memory tangible and tradition enduring.

Discussion

Start the conversation

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts on this article. Your insights could spark an interesting discussion!